An Apology For The Books Of Dan Brown

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

There’s a quiet, cozy center in the human brain that Dan Brown’s novels have a great way of probing that the movies can’t.

There’s a quiet, cozy center in the human brain that Dan Brown’s novels have a great way of probing that the movies can’t.

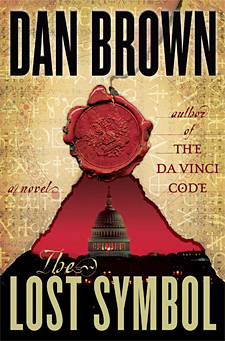

It is around that center that I’ll base my brief apology for his novels. Full disclosure: I haven’t read The Lost Symbol yet, and although I’ve read Deception Point, I’m really only talking about the Langdon novels here: Angels & Demons and The DaVinci Code.

The opening scene of The DaVinci Code takes place in the Louvre Museum in Paris at night. That’s a simple choice, but despite Brown’s lackluster prose, my imagination was able to conjure up a glimmery setting aglow with candles, track-lighting and intrigue.

It’s hardcore guilty-pleasure material, right down to the intellectual hokum at the center of the stories. The DaVinci Code deals with an ages-old conspiracy to conceal the true nature of Jesus Christ, and besides the idea that Christ was human (which I’ll accept as an axiom), he played fast and loose with a great deal of shadowy, lurid, secret-society-style notions that there are great, unknown forces at work in our world.

Angels & Demons, which technically takes place before DaVinci (although the movie reversed their order), is essentially the exact same book. Brown fancies Langdon a geek’s Indiana Jones, and that’s fine with me. The character as described in the novels is just a proxy for Brown himself, who by all accounts is a goof.

He rightfully gets a lot of grief for his laughable writing. The UK’s Telegraph assembled a list of his 20 funniest lines, but I’ll single this one out:

“Captain Bezu Fache carried himself like an angry ox, with his wide shoulders thrown back and his chin tucked hard into his chest. His dark hair was slicked back with oil, accentuating an arrow-like widow’s peak that divided his jutting brow and preceded him like the prow of a battleship. As he advanced, his dark eyes seemed to scorch the earth before him, radiating a fiery clarity that forecast his reputation for unblinking severity in all matters.”

As a fiction-writer myself, I’ve never seen much use in ascribing a single characteristic to a character’s eyes. It’s a cheesy device, as Brown demonstrates here, but more than that, it’s just not accurate. People don’t always have the same look in their eyes. The density of their expression changes depending on the situation.

But back to Brown as a guilty pleasure: Brown invites readers on rollicking geek-fests through ancient literature, dusty libraries and creepy old temples. Like his forebear Indiana Jones, Langdon is a non-religious hero in a religious world, and I find that compelling for personal reasons.

His books are cozy fun. The movies not so much.