Future Fragments: Pop Academy

Written by: Anastasia Salter, Pop-Culture Editor

I’ve just returned from a weekend in San Antonio, Texas for the Pop Culture Association’s national conference. Pop culture’s shown a lot of love for academia lately, with shows like Community putting college professors on the map. But depictions of academic conferences usually start and end with scenes like the Friends episode where Ross brings everyone with him to a paleontology conference that happens to be on a tropical island. The reaction of the decidedly non-academic Friends to the excitement of “dinosaur geeks” gathering for a keynote was priceless, and indeed most conferences are filled with similar jargon and in-jokes. A pop culture conference holds the promise of embracing the slightly less obscure.

Pop culture scholars, unlike scholars of “Literature” (the capital L, of course, implying endorsement from the appropriate authorities), don’t show up much in pop culture themselves. Dawson’s Creek featured one, Prof. Matt Freeman as played by Sebastian Spence, whose role was mostly to help other characters struggling with their sexual identity. The lessons of his subject were turned into tools for understanding self–a fine message for a TV show, perhaps, but not so much of a mandate for the future of a profession.

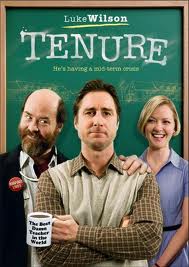

A not-often-remembered film, Tenure, starred Luke Wilson as a professor in an English department facing the competition for tenure at a small university. The story follows a great teacher who isn’t so keen on the other responsibilities of academia–namely, that “publish or perish” part. The ritual of seeking academic journals to publish in is excruciatingly followed as he submits to progressively less and less prestigious spaces seeking acceptance. This is the portrait of the traditional scholar, living a mostly pre-digital life of isolation. It’s a perfectly depressing portrait of the worst parts of academia, from faculty rivalries to petty battles for attention.

The conference schedule was packed with Joss Whedon sing-a-longs, poker walks, tweet-ups, endless ironic pop culture t-shirts and enough papers to fill a Norton’s Anthology with titles alone. (Can’t picture it? Check out the program). It’s one of the few places you can go and find, for instance, a whole series of panels devoted to Doctor Who right along-side a series of panels on Motorcycle Culture. And, memories of academic conventions as portrayed on TV aside, it can look a lot more like a fandom gathering than an academic conference if you catch it at the right moment. Hashtag backchannels like PCA’s #pcaaca11 look a lot like the #Glee chat advertised on Fox while the show airs, though with fewer voices and (usually) fewer exclamation marks.

Looking at pop culture isn’t usually thought of as an old discipline, though you could make the argument that as William Shakespeare was a pop culture producer of his era, repackaging bits of familiar stories with a good dose of wit and period in-jokes, it’s a lot older than anyone gives it credit for. And as for the argument that “old” pop culture is better somehow than the new stuff, that’s debatable. Steven Johnson took on the TV-haters with his book Everything Bad is Good for You, which pointed out that pop culture is getting a lot more complicated. The intertextuality in an episode of Family Guy alone is worthy of the attention both of fans looking to get in on the joke and scholars interested in capturing a cultural moment–and sometimes, the two activities look a lot alike. There’s nothing new about fans in academia: Henry Jenkins is credited for the term “aca-fan” which nicely sums up a dual identity that isn’t quite worthy of Clark Kent.

The objects under discussion at the PCA event were the same objects we take in every day: Stargate. Soap Operas. Glee. The sheer numbers of academics interested in traveling to a conference for near-continuous conversation is a testament to how much is going on. Academia may seem isolated–the depiction of the professor in a secluded office mostly undisturbed by the outside world remains a powerful one. It’s true that most of us will never hear all the papers at PCA: indeed, even attending in-person it’s an impossible task to take in more than a tiny fraction. But the topics raised are a reflection of where we are, and where we hope we are heading. Take the analysis of the corporatization of AIDS rhetoric, for example, or the many many arguments over gender and gaming. Fans and academics finding the diamonds (and the duds) in an endless stream of media saturation have a lot to say to eachother, and even more to complain about. As more social tools like Twitter bring everyone in the same place, perhaps we’ll even see a future that doesn’t involve so many scholars in their bubbles.