In Praise of the Classics: Homer’s Iliad

Written by: Tony Lazlo, CC2K Staff Writer

CC2K’s Tony Lazlo looks back at Homer’s classic.

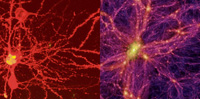

I invite you to look at the picture to the right.

Astrophysicists used computers to generate the image on the right half of the picture, which is a representation of the current universe. To scale, it measures hundreds of thousands of light-years across.

On the left is a photo taken of a single neuron from the brain of a mouse. To scale, it measures a few microns across.

Like fractal geometry, these two images reveal patterns that emerge from the natural universe. When I look at these two images, my mind does delicious backflips because I’m peering into the superstructure of reality as we know it. In the same way, when I read Homer’s Iliad, I’m peering into the superstructure of storytelling as we know it.

I stress the noun superstructure because I want to call to mind the image of great titanic behemoths striding out of dense fogs and swirling sandstorms. I want you to imagine tentacled leviathans emerging from 20-foot waves. And I want you to use your imaginary eye to peer past these great mythological beasts into the elemental depths from whence they came – and see the mighty, hairlined, grimy bones of the earth.

We’ve all seen the cover of the popular trade paperback edition of Joseph Campbell’s Hero With A Thousand Faces and how it sets Luke Skywalker alongside the ancient heroes of old. I get misty-eyed just looking at that cover, because I’m so fucking proud that we have Luke Skywalker. Say what you want about the prequel trilogy, George Lucas’ goofball farmboy-turned space samurai is kin to Homer’s Achilles, the prima-donna demigod who comes out of retirement to avenge the death of his lover.

When you read Homer, you can sense the giddiness of some of our planet’s first great storytellers as they made connections between plotlines that would become fundamental ebbs and flows of all stories to come. Where would literature’s cuckolds be without hapless Menelaus? Where would literature’s sensitive lovers be without the fey, crafty cocksmith Paris? Where would literature’s overreaching military leaders be without Agamemnon? Where would literature’s old sages be without Nestor? Where would literature’s lead-brained heavies be without the Achaian wall, Ajax? Where would literature’s geniuses be without the brilliant, cunning Odysseus?

And let’s not forget about the gods. Naturally, the Greek pantheon is a major player in Homer’s narrative, and by including them, he laid the groundwork for all sci-fi and fantasy writers to come by establishing the rules for his super-powered characters and following those rules.

I’m not familiar with the authorship of The Iliad, but I suspect that like the works of Shakespeare, we’re looking at the work of many oral storytellers that one sublime writer united.

In his intro to this series, Rob Van Winkle rightly pointed out that far from being boring, most classics include all manner of fun, lurid depravity. The Iliad is no different. Nary a page goes by without brain matter exploding out the eyeholes of some poor bastard’s helmet. In fact, where the Jewish Tanakh (Christianity’s Old Testament) has page after page of names linked by births, The Iliad has page after page of names linked by exploding brains.

Moreover, Homer tells his story with language and plot points as powerful as judo chops to the sternum. To wit, let’s talk about the face that launched a thousand ships, Helen. Simply through pop-culture osmosis, we know that Helen is beautiful, but if we go back and actually look at the text, we find out that Helen is a hell of a lot more than just beautiful.

A Trojan elder talks about Helen in the Richmond Lattimore translation:

Surely there is no blame on Trojans and strong-greaved Achaians

If for long time they suffer hardship for a woman like this one.

Terrible is the likeness of her face to immortal goddesses (III, 156-159).

OK, let’s break down this passage. At first glance, it looks like the old guy is saying Helen is ugly, that she bears a terrible likeness to a goddess. But remember that the word “terrible” shares DNA with the word “terrify,” which links it to an old-world use of the word, which meant fearsome, in the grand, Old-Testament sense.

In other words, the elder is saying that Helen looks so much like a goddess that she’s fearsome to behold. The elder is saying that if you’re not a great man like an Achilles or an Agamemnon, you would cower before Helen’s beauty. Looking at Helen is like looking at the fucking sun.

And just to drive home the power of Homer’s words, let’s look at the same passage in Stanley Lombardo’s loony, galloping translation, which he wrote for stage performance:

Who could blame either the Trojans or the Greeks

For suffering so long for a woman like this.

Her eyes are not human.

Whatever she is, let her go back with the ships (III, 164-167)[.]

Awesome. Look at how Lombardo takes the “fearsome resemblance” idea and spreads it out over two lines. He makes the dramatic choice to endow Helen’s eyes with hypnotic powers and uses the words “whatever she is” to further enshroud her with dread.

But fuck all that and listen to why you should read and delight in Homer’s mighty legend.

The Iliad will infect you with joy because it will invert your idea of Greek mythology. It did mine. I grew up with the randy, gallivanting myths from the Edith Hamilton wing of mythology – all the grand old tales about Zeus knocking up every other babe and Hercules slam-dunking his impossible tasks. I used to think that Greek myths were about the childish non-people who inhabited Mount Olympus.

They’re not.

I realized this near the end of The Iliad, when Homer recounted a brief story about an old Trojan guard who hears that Achilles has emerged from his tent and is currently steamrolling his way around the walls of Troy. I forget the exact passage, but a bunch of other Trojans tell the old man to run, but he doesn’t. He thinks to himself something like, “Well, I’m going to die, but at least I’m going to die on my feet.”

I had to set the book down for a moment after I read that scene, because I felt so bad, so embarrassed that I hadn’t realized sooner that for all this time, the Greeks myths were about people.

Don’t make the same mistake I did. Read The Iliad now and meet the people of ancient Greece. They look a lot like us.