Memoirs: The Reality TV of Literature

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

Few (if any) literary genres have experienced a surge in popularity over the past few years like the memoir has. And yet—and I mean no offense to anyone who is a fan of the genre—memoirs are, by and large, self-indulgent pieces of crap.

Few (if any) literary genres have experienced a surge in popularity over the past few years like the memoir has. And yet—and I mean no offense to anyone who is a fan of the genre—memoirs are, by and large, self-indulgent pieces of crap.

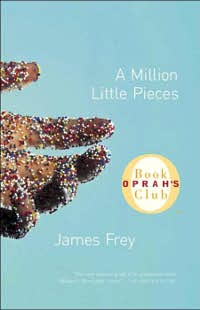

Memoirs are usually written for one of three reasons. If they are written by celebrities, they are usually tools for that person to capitalize on his/her fame to make a few bucks. If they are written by has-been celebrities, they are usually a way for that person to try to recapture his/her former glory. And if they are written by a non-famous person, they usually exploit some circumstances of his/her life (crappy childhood, abusive parents, poverty, drug abuse, etc.) to get the author fame, notoriety, or a big fat paycheck—usually all of the above. Top that off with all of the fabricated memoirs that have been published in recent years (A Million Little Pieces being the most famous example, but there are many others), and you have a genre that is ripe with corruption and abuse.

Is there ever any value to publishing a memoir? I think there can be. Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl offered powerful, moving insight into the life of a young girl hiding from the Nazis during World War II, and the literary world would be lesser without it. But Anne didn’t write the diary with the intention of publishing it; this came only later, after her death. But most memoirs are written with publication in mind, and my sense is that the tendency toward self-aggrandizement usually undermines any literary merit they have.

If the following rules were universally followed, most of the crappy memoirs in the world could probably be removed from the shelf.

If you’re going to write a memoir, you should probably be old. If you’re going to have the audacity to say that your life experiences give you insight to comment on the world and life, you’d better be old enough to have those experiences. Otherwise, it’s just sheer arrogance. Elizabeth Taylor’s memoir could be interesting. Paris Hilton’s memoir—and sadly, there is one—not so much.

Do you have a unique insight into history? Although not a memoir in the traditional sense, Anne Frank’s diary breaks the rule about having to be old before you can write an interesting and important memoir. But it works because it gives us insight into a part of history—the Holocaust, and the plight of Jews in World War II-era Europe—that we cannot experience for ourselves.

But bear in mind that the “unique” part of the equation cannot be separated from the “historic.” I remember 1989—the year the Berlin Wall fell—quite vividly. Does that mean I should write a book about it? Not unless my experiences as a first grader in Pittsburgh somehow give me a unique take on the end of the Cold War. (Here’s a hint: they don’t.)

Drug addictions do not equal memoir material. Neither does poverty, bitterness toward your parents, or any of the tales of woe that line the Barnes and Noble bookshelves. We’ve all got crap in our pasts. If you feel the need to share it, go see a psychologist.

When you make stuff up, it’s called fiction. James Frey was ridiculed in the publishing world a few years ago when his memoir, A Million Little Pieces, was found to be largely exaggerated. More recently, Misha Defonseca admitted that her 1997 memoir, Misha: A Memoire of the Holocaust Years, which chronicled her life as a Holocaust survivor who trekked across Europe and lived with a pack of wolves, was entirely fabricated. There’s nothing stopping you from making stuff up, as long as it’s on the fiction shelf. In this overly mediated world, do you really think that someone won’t discover your fabrications? When you write a memoir, Big Brother really is watching, waiting to find any factual inaccuracy that will expose you as a fraud.

The bonus here is that writing fiction makes it a lot harder for people to sue for libel. So if the “fictional” mother of your protagonist makes Joan Crawford look like June Cleaver, all you have to do is say, “No really, Mom, this is just an imaginary character.” (Be warned, though: that won’t stop them from cutting you out of the will.)