The Problem With Flawed Heroines

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

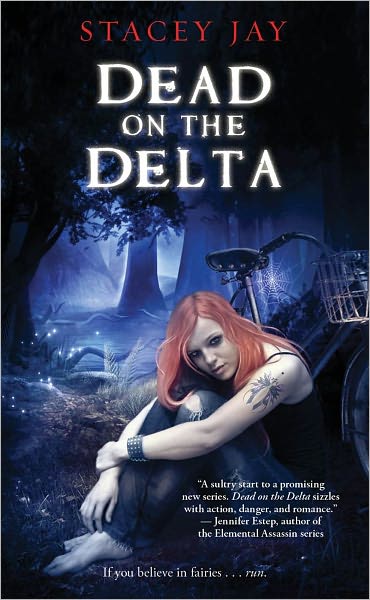

In the wake of Amy Winehouse’s death, Stacey Jay—author of the urban fantasy novel Dead on the Delta—wrote a blog entry talking about how her protagonist, Annabelle Lee (who was an alcoholic), had been called a “train wreck” by some readers because of her addiction. It was part of a larger train of thought, about how addictive behavior by females is viewed and treated differently than the same behavior by males. But I think it’s part of a larger problem, in books and in society itself.

In the wake of Amy Winehouse’s death, Stacey Jay—author of the urban fantasy novel Dead on the Delta—wrote a blog entry talking about how her protagonist, Annabelle Lee (who was an alcoholic), had been called a “train wreck” by some readers because of her addiction. It was part of a larger train of thought, about how addictive behavior by females is viewed and treated differently than the same behavior by males. But I think it’s part of a larger problem, in books and in society itself.

One of the things that drives me nuts about female characters is that they’re often relegated to “socially acceptable” roles and mores. There is a double standard by which characters are judged. For a male character, it’s okay to be an addict, to be violent and angry, to be promiscuous, to be on the wrong side of the moral divide, and still be a hero. Female characters who exhibit the same type of behavior are viewed as screws ups and sluts.

As a result, many of the females you see in books are limited to “acceptable” behavior, because when they stray from that, they risk alienating readers. Look at Wuthering Heights. Heathcliff—a liar, thief, and murderer—is the “Byronic hero” of the piece. Cathy, who does nothing worse than enter into an ill-advised marriage with someone she didn’t love, is viewed as nothing more than the bitch who screwed him over. Heathcliff is only the way he is because of Cathy. Not that either character is exactly upstanding; both Heathcliff and Cathy repeatedly do selfish things that hurt the people around them. But if you look at their actions objectively, Heathcliff’s offenses are worse than Cathy’s. Yet Heathcliff has been romanticized by readers and Cathy villainized.

It’s something I struggle with both as a reader and as a writer. When I was in college, I wrote a short story about a women in an unhappy marriage who found herself attracted to another man. When I brought the story into my writing workshop, my heroine was criticized and called unsympathetic by several students—not for her actions, but just for her thoughts. Apparently, even thinking about cheating on her husband was too much.

In my current work-in-progress, my heroine is a killer. I wrote it knowing that, no matter what other things she did, there would always be readers unable to sympathize with her because of her behavior. Which is fine, but I have to wonder how many of them are alienated solely on the basis of her actions, and how many are alienated not only because of her actions, but because of her femininity.

But when it comes down to it, book characters are fictional. What worries me are the parallels between the way we view fictional book characters and the way we view real people, Winehouse being a prime example. After Winehouse’s death, there was this undercurrent that her death was her fault, that she should be made an object of contempt because of her weakness of character. As Stacia Kane, author of the Downside Ghosts series (whose drug-addicted heroine has been subjected to the same type of ridicule), where was this contempt after Kurt Cobain’s death, or Charlie Sheen’s very public downfall?

I’m not sure what I’m arguing here. Certainly, I can’t tell you that you should like or sympathize with every book heroine you encounter. But I do think reactions to female characters are worth further examination, to know whether the reaction is on the basis of the character…or the gender.