The Symptoms of Literary Sexism

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

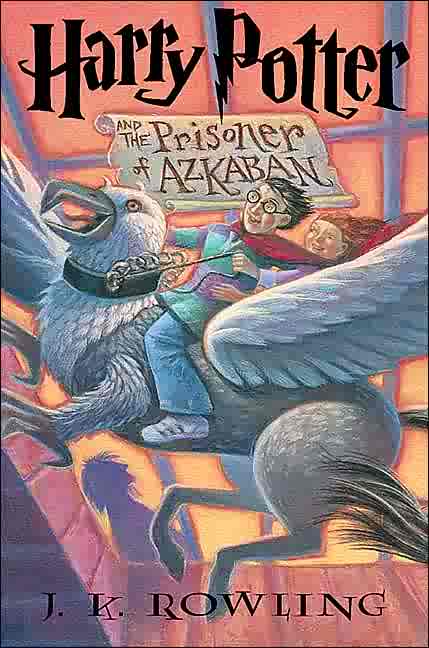

For a long time, I’ve had this feeling that women were getting the short end of the stick in literature. But I didn’t have any way of confirming it. After all, J.K. Rowling and Stephenie Meyer are two of fiction’s most recent success stories.

For a long time, I’ve had this feeling that women were getting the short end of the stick in literature. But I didn’t have any way of confirming it. After all, J.K. Rowling and Stephenie Meyer are two of fiction’s most recent success stories.

Then I saw these statistics.

But wait. Maybe women just didn’t publish as much in 2012 as men. After all, we can’t expect that the numbers will be exactly equal. Except we have the three year comparison here.

But wait. Maybe women just don’t publish as much literary fiction and nonfiction as men. After all, some women are certainly covered in these magazines. Thing is, even when women are covered, they are often not afforded the same amount of coverage as men.

But wait. Maybe it’s just “literary” fiction and nonfiction. Maybe women excel more in genre fiction. Except we have this study, which shows that women’s books are reviewed significantly less, and women make up fewer of the reviewers, than men, in prominent science fiction and fantasy magazines.

So why does this happen? After all, as I’ve argued before, correlation is not causation. Just because men comprise more of the reviewers than women, and male authors are reviewed more frequently than female authors, doesn’t mean that there’s a bias against women in the literary world. Maybe men just write better books. In 2011, Nobel Prize-winning author VS Naipaul declared, “I read a piece of writing and within a paragraph or two I know whether it is by a woman or not. I think [it is] unequal to me,” because of women’s “sentimentality, the narrow view of the world.”

Nothing to see here. These aren’t the droids you’re looking for. Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.

I call bullshit.

Let me make something clear: I don’t believe that there’s some vast conspiracy going on here to get women out of the literary world and send them back to the kitchen. But I do think there are implicit biases at play here.

In the Western world, being white, heterosexual, and male is considered the norm, almost a lack of a cultural identity. Their experiences are afforded a kind of universality that other genders, races, and sexual orientations aren’t given—even if they’re writing protagonists that fall outside of their own race, gender, or sexual orientation. Meanwhile, though “masculinizing” the names of female authors may sound like a relic of the 19th century, it’s not: J.K. Rowling’s publishers demanded she use initials rather than her first name, Joanna, because they believed boys would not read her books if they knew they were written by a woman.

What’s insidious about sexism in 2013 is that it’s often difficult to pinpoint. It’s not rules or laws that are keeping women down, but people’s subtle—and often unacknowledged—biases. In 2010, when authors Jodi Piccoult and Jennifer Weiner protested against this favortism, there was a lot of backlash against them. After all, they were “just” commercial writers. Their work wasn’t good enough to grace the pages of The New York Times literary section.

But that was never the point. The point is that there is a bias, and it’s too pronounced to be explained away by just coincidence. If we ignore it, or if we try to rationalize it, we let the people who truly believe men’s writing is inherently better win.