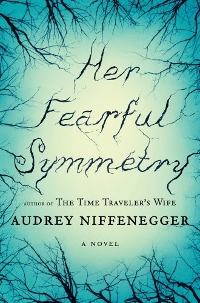

When Good Books End Badly: Audrey Niffenegger’s Her Fearful Symmetry

Written by: Beth Woodward, CC2K Books Editor

I recently read Audrey Niffenegger’s long-awaited second novel (after the 2003’s bestseller The Time Traveler’s Wife). Although it’s not as exciting or plot-heavy as Niffenegger’s first offering, Her Fearful Symmetry is more atmospheric, a stunning portrait of London–especially the famous Highgate Cemetery, which is described in rich detail. The novel is also a melancholy meditation on love and loss, relationships and identity. And if you had asked me while I was reading the beginning and the middle, I might have even said that, in its own way, Symmetry might be a stronger book than The Time Traveler’s Wife.

I recently read Audrey Niffenegger’s long-awaited second novel (after the 2003’s bestseller The Time Traveler’s Wife). Although it’s not as exciting or plot-heavy as Niffenegger’s first offering, Her Fearful Symmetry is more atmospheric, a stunning portrait of London–especially the famous Highgate Cemetery, which is described in rich detail. The novel is also a melancholy meditation on love and loss, relationships and identity. And if you had asked me while I was reading the beginning and the middle, I might have even said that, in its own way, Symmetry might be a stronger book than The Time Traveler’s Wife.

Then I got to the ending. And that feeling that the book had built up inside me over the first 400 pages was killed within the last 50. Though some may have disliked the ending of Time Traveler’s Wife–and Tony Lazlo certainly made a compelling argument as to why–I always believed it felt true to the spirit of the book. But Symmetry shifts tone so dramatically, and characters act so differently, that it’s almost difficult to believe that the same person wrote the book from beginning to end.

I believe that endings are the most important part of a book. The beginning of a book may be what hooks you in, and the middle is what keeps you going, but it’s the ending that lingers, the part that stays with you the longest. A kick-ass ending can turn an otherwise okay book into a good one, and nothing can make a good book go bad like a lame ending. Unfortunately, Symmetry falls into the latter category.

But maybe I should start at the beginning. Elspeth Noblin, a middle-aged woman who lives near London’s Highgate Cemetery, dies of leukemia. She is unmarried and childless, and she had been estranged from her twin sister, Edie, for decades. As such, Elspeth leaves her entire estate–including her flat–to her twin nieces Julia and Valentina, with the stipulation that they may only sell the flat after they have lived there together for at least a year. When the twins arrive in London, they move into their aunt’s apartment and start meeting her neighbors: Martin, a kind mind battling severe OCD and unable to leave his apartment, and Robert, Elspeth’s younger lover whose visceral grief overwhelms him. But although Elspeth is dead, she is not gone; her ghost haunts the apartment, and soon the twins begin to feel the effects of her presence.

The best moments of this book are the small ones: the longing Elspeth feels to be alive again, Julia’s growing devotion to the isolated Martin, the tentative bond formed between Valentina and Robert. Niffenegger has a talent for describing the small details that make us human, both the beautiful and the ugly. She employs that well here.

So how does it all go wrong? Without saying anything spoilery–just on the off chance that you still want to read the book after this critique–let’s just say that, in the end, the characters act in ways that simply don’t make sense, given what we had learned about them up until that point. The result is an ending that simply feels false, as if it doesn’t belong with the rest of the book.

Suspension of disbelief is very important when a story delves into the supernatural, but it’s not in the supernatural elements where I felt myself unwilling to go along for the ride. If I can’t believe in the characters, how can I believe in the story?

It’s a shame, too: Niffenegger is a talented writer, and I’ve been waiting a long time to read this book. But hopefully Niffenegger’s next offering will live up to the author’s promise.